True Artisans, Preserving Spain's Ways

March 2011

“Artisan” is a word that we often use to describe many of La Tienda’s products. By purchasing from families of Spanish artisans, we encourage them to continue their traditional ways of making products by hand. The fruit of their labor is the continuity that nourishes the soul of Spain. For us artisan is far more than a romantic marketing term designed to catch the eye -- it is the core of what we do as a family, and we take this concept very seriously.

We are in a world that is so media savvy that anything of perceived value is fodder for marketing. After a while, we learn to be skeptical of nuanced marketing words.

Currently every breakfast cereal from All-Bran to Count Chocula trumpets a whole grain label. So what does “whole grain” mean? Are Cocoa Puffs and Shredded Wheat equally noble breakfast cereals?

Moreover, when I look at the food facts listed on the carton of my favorite "all natural” ice cream I see many strange terms listed in addition to cream, eggs and fruit. Of course, I think the most amusing misuse of labeling is the one proclaiming fat free half & half! For each of us as consumers, it becomes an issue of credibility.

I was thinking about this credibility gap on my flight home from Spain. My wife Ruth and I had just spent a couple of weeks in Spain renewing friendships and visiting families who provide products to La Tienda. We visited true artisans in every sense of the word. I would like to tell you a little more about a couple of them, so that you will understand what my sons and I mean when we at La Tienda use the term artisan. These people are the salt of the earth.

It was late Friday afternoon when our plane landed in Palma de Mallorca. Our good friend Carmen met us at the airport. She was visiting with her father as she does with great frequency now that he is older, but took the time to be with us. As we drove through the streets of Palma, she pointed out various sites that reminded her of her happy childhood in Mallorca. Now she and her husband Juan Carlos own a boutique bodega in El Puerto de Santa María.

Armed with a Tom Tom GPS, we headed toward one of the small villages on the island where Bernat Fiol and his son fashion bowls and plates from olive wood in their workshop. Alas, our GPS Wizard Tom Tom disappointed us as he often does, and we found ourselves winding through nearly identical narrow streets that were randomly identified with street names painted on the walls. To make it more challenging we discovered that some of the streets have two different names!

At any rate, thanks to several of Carmen’s inquiries in the Mallorcan dialect, we found number 12 to the right of the doorway and rapped on the metal door. From inside Bernat’s son, a young man also named Bernat, opened the garage door and welcomed us into the family workshop. As you might imagine, the place was covered with sweet smelling sawdust generated by their labor each day. It was a crowded room, with a pile of discarded pieces of olive wood to the fore, shelves of drying olive wood products to the left, and a considerable amount of olive wood planks of various thicknesses to the right. He explained to us that these planks of olive wood had to be imported from the mainland by ship, since the endangered olive trees native to Mallorca are protected.

It did not make much sense to me that what is being chopped down in one place was protected in another, but Bernat explained that it was a matter of economics as well as ecology. At present, there is a glut of ordinary olive oil on the market bringing prices so low that it is hardly worth the labor required to produce it. In addition, as olive trees get older, they produce less fruit, making them less valuable for the production of oil. Their commercial value is in their smooth beautifully grained wood, formed through sometimes centuries of growth.

The thickest broad planks in the workshop are milled from trees that are hundreds of years old. Bernat and his son reserved these prized pieces of wood to make large items such as big salad serving bowls carved out of one piece of wood. Because of the scarcity of wood of this size, Bernat and his father may make only five or six a year. They could laminate various pieces of olive wood together to give the appearance of solidity, as many other producers do, but as artisans who take great pride in their work, they would not dream of cutting corners in this way.

About this time, Bernat's father appeared. He was a hearty, welcoming man -- I would guess about in his late fifties. It was he who chose the life of a wood carver, and his only son works with him every day to make these beautiful products. This tradition of father passing on his skills to his son stretches back to biblical times.

He took a piece of wood and asked us to follow the process from beginning to end. As he explained the process to me it became clear how labor-intensive it was, and why the end result is so costly. Bernat and his son always use green olive wood, because it is easier to work with and to shape.

First, he selected a piece of olive wood and imposed a template on it so he could rough out the size of the finished product. Next, after refining the exterior shape, he gouged out the interior with special tools, putting the personal touches on the piece by deftly chiseling its lip and the foot. Bernat explained that at this stage they immerse the piece in a special water bath for up to two days before placing it on the shelf by the door, a location that will assure slow drying. This assures that the pores of the wood are closed, and minimizes the possibility of the wood cracking.

About two months later, they soak the dry olive wood bowl in mineral oil for about a day to prepare it for the final artisan touches. Father and son polish each piece by hand, using steel wool and sand paper. More than two months have elapsed from start to finish even for the most humble spoon or the grandest bowl.

By then it was getting dark outside, but as we were preparing to leave the younger Bernat proudly confided that he and his wife were expecting their first child in the spring. Bernat and his son and daughter have lived in this town all of their lives – his wife comes from a neighboring village. The externals of life do not change too much for the Fiol family. Their focus is on what they have done for years as artisan wood carvers. Yes, they now use some electrically assisted tools and even a computer. Nevertheless, the essence of their lives remains intact. When we call their work artisan, you know it is the real thing.

A few days later in our journey, Ruth and I stopped by another kind of workshop, a rural one – a few miles from Córdoba (and not far from the town where the matador El Cordobés was born).

Lola and her friend Angela had emailed me about the new recipes they were excited about, and wanted us to drop by their kitchen to evaluate their new creations the next time we came to Spain. As they ushered us into the modest metal warehouse, I greeted Ana, a cheerful middle-aged woman who was squeezing plump lemons by hand, one by one. Not far from her was her neighbor, Amalia, who tended a machine that was chopping olives for a new tapenade. A few feet away Paqui was preparing the canning jars.

There are five women in all who make pure homemade soups and sauces, originally to help their working sisters in the neighborhood. They get up before daybreak so that they can complete their labor in time to pick up their children from school in the early afternoon.

Lola ushered us to a long table in the back of the structure where she and Angela had prepared a variety of new recipes for us to sample. Among the creations they presented us with was a series of cremas, traditional pureed soups, they were developing. I won’t go into detail until we are able to get them to your table. The flavors are exquisite, and I could visualize many applications for the creative chef.

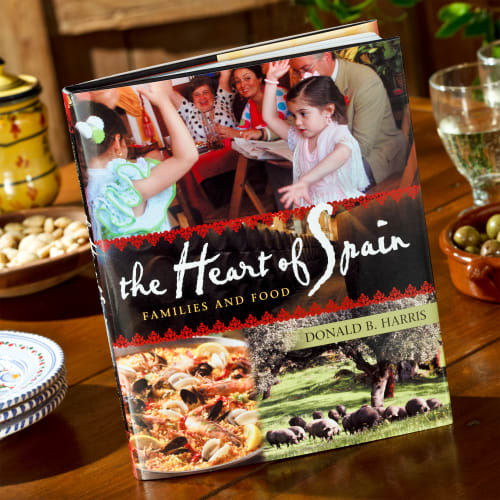

As I hope you can see, for our family artisan is the real thing, not some nuanced marketing term. It is a source of pride for us; providing the best in Spain delivered from the hands of her people. You can meet more of our artisan friends in my newly published book, The Heart of Spain (a shameless plug!!), within whose pages you will meet other families and the food they share.

¡Buen provecho!

Don